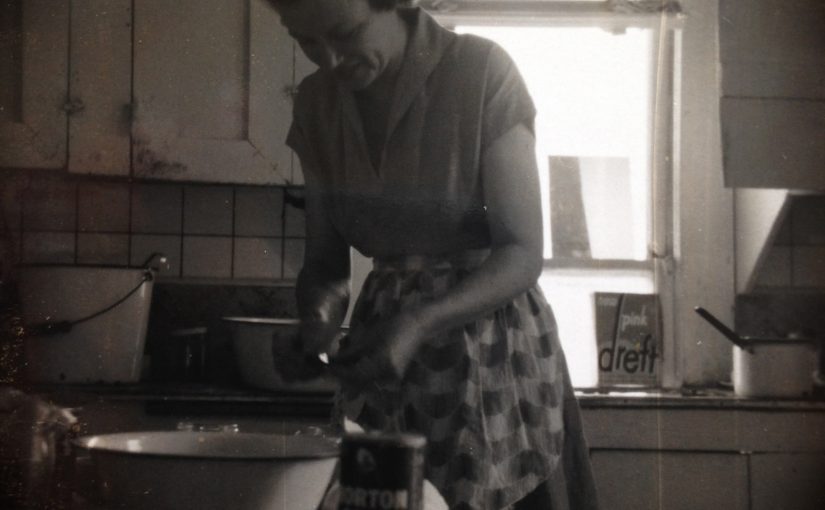

My grandmother, Lois was a beautiful woman. She wore simple dresses that she made herself on a old treadle Singer sewing machine. Her thick, brown hair waved around her sweet face, except for the strands she managed to keep off her forehead with bobbie pins. She had a figure any schoolgirl would envy: a stomach so flat her skirts hung from her tiny waist the way they would on a runway model. The colors of her clothes, as well as their cut and form, were modest. She tried not to call attention to herself. She was quiet and hardworking. She was my definition of “Good”. She was a Christian woman and she didn’t have to proclaim it. You could see it, everyday, in her simple life as a farmer’s wife. She was everything I wanted to live up to but always seemed to fall short.

Maybe, I have her built up in my mind more perfect than she really was. Still, I like to keep her like I have her stored there. She seemed almost angelic. She suffered much in her short life. The amenities that I take for granted, she never had. I could fill a book on her life but I will try to tell the story I meant to tell: my last living memory of her.

Our family had gone to her house, along with my mother’s brother, Tommy and his family, for some holiday. I can’t remember, now if it was Easter or Mother’s Day. I picture the three women (Grandmother, Momma, and Aunt Wanda) along with my older sister, Tina and me. We were in the west bedroom of her Victorian gingerbread house. My grandmother had called Momma and Aunt Wanda in there to show them some pictures. Tina and I had tagged along. I sensed some importance in this meeting. We circled the bed like tribal women surround a fire, eyes forward, ears listening. I was the youngest.

Laid out on the bed were old, framed, black and white photographs. Some were of my grandfather shockingly handsome and young with his basketball team all lined up on the black-land dirt. Their uniforms neat and almost modern looking. His hair in sunlit waves brushing the forehead above his sparkling, mischievous hazel eyes. Some were of their small school; children lined up at its rustic sides according to age and height. So few they were that the whole school could be fitted within the frame of the photographer’s lens. Some wore fancy, frilly dresses with bows almost as big as their heads tilting heavily to one side of their wavy bobs. Some wore overalls and freckles, but no shoes; toes displayed proudly. The teacher stood off to one side; clean, polished, an example of the education they would receive and the ethics they would learn.

I realized how somber Grandmother was. This was serious to her. She pointed to a couple of pictures that I had seen lying on the chenille bedspread but had averted my gaze from. Now, as they were forced to my attention, I realized the weightiness of the images. There, in a fancy coffin was the creepy, emaciated remains of my great-great grandmother. I was revolted by the thought that someone would take a picture of a loved one in their deceased state. Why, I thought, would anyone want to remember someone that way? Wouldn’t you want to remember them with a smile on their face and laughter in their breath? Momma and Wanda felt the same. We were united in our disgust.

Grandmother spoke in her quiet way. She told us that she had always hated the macabre pictures herself, but her mother had made her promise to take care of them. She was a good daughter and had honored her mother’s wishes, storing them away out of sight. This was what she had brought us together for: to exact a promise from her own daughter. I was witness, along with the others, of the promise Momma made to her. When she died, she wanted Momma to take the funeral photos and burn them.

This request was like an exclamation point on that day because it was on that day that I saw her take my mother’s hand and place it on her swollen belly. I had not noticed in my youthful mind that there had been a physical change in her. I had ignored her lack of energy and the way the natural dark circles around her eyes had darkened. I saw, then, Momma’s eyes widen as she felt the knot beneath her hand. Grandmother asked her if she felt it. Momma nodded. Wanda reached out her hand to feel as well. She, too, felt the tumor. In unison, they pleaded with her to see a doctor. Soon, she did. Our lives were never the same.

I vaguely remember going to see her as she lay in her eastern room, dying. I’m not sure if it really happened or not. I think Momma tried to protect us from witnessing the pain she was going through. Maybe she was caught up in taking care of her and didn’t realize we might want to see her. I know I was not there when she passed from this world. Momma was. It was Momma’s birthday. She came home from the hospital for the supper and cake we had made for her. She returned to the hospital and was with her beloved mother that night when she slipped from this dark world.

I’ve run her passing over and over in my mind. What if someone had been willing to loan her the money for an operation years before…what if they hadn’t been farmers…what if she hadn’t wore herself out taking care of everyone but herself.

This I know:

My grandmother took care of her mother when she was deathly sick herself. My grandmother was a good wife. My grandmother was a good mother. I will continue to put her on a pedestal and try to be the daughter, mother, grandmother, and wife that she was. I pray that the Lord would put in me whatever He put in her that I might attain it. I love you, still, my grandmother.